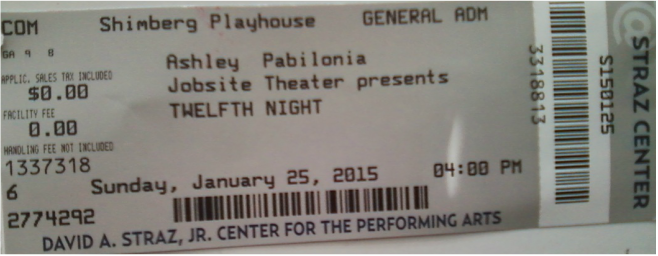

by Ashley Pabilonia, with contributions by Stephanie Whitehall

Jobsite's "Twelfth Night" promotional banner.

Jobsite's "Twelfth Night" promotional banner. Having grown up in the Tampa Bay area and enjoyed my college years attending the University of Tampa, which cultivated my love for literature, Jobsite Theater's decision to set their rendition of Twelfth Night in 1920s Ybor City interested me. A piece of canonical theater played out in a local landscape and in an era romanticized as much for its jazz music and fashion as its underbelly of drunkenness and crime? The setting was poised to tell as much of a story as the text itself.

That said, I was wary about this play being, well, Shakespeare. The Bard has a reputation of haunting students in literature classes with illustrious dialogue that might as well be its own language. As excited as I was to see a play set in a locale that endeared me, I was unsure whether I would be able to understand what was even going on in the play.

I understood the skeleton of the story: Viola was disguising herself as a young man named Cesario to get close to Orsino, who insisted that "he" convince Olivia to return Orsino's affections. In the process, Viola had fallen for Orsino herself, and Olivia became attracted to Cesario. Olivia's louse of an uncle Toby was having fun hanging out and drinking with this Andrew guy. There was some other Cesario-looking guy who popped out of nowhere telling his companion Antonio he needed to go to Illyria (that is, Ybor City). Oh, and for some reason Olivia's handmaiden Maria wanted to make a fool out of the steward Malvolio by tricking him into thinking the lady he served secretly harbored affections for him.

What I was missing was the context. Somewhere in the characters' fanciful conversations, I should have figured out that our hero/ine Viola had survived a shipwreck (caused by a hurricane that slammed Miami while she was en route from Cuba, in this rendition), which led her to seek Orsino (a bootlegger) for work under the guise of Cesario. The guy that looked like Cesario was Viola's twin brother Sebastian, who also escaped the wreck, and Antonio a sea captain who had previously wronged Orsino's court. Andrew himself was interested in courting Olivia (whose "old money" status probably attracted many a man), and he would have left sooner if Toby hadn't tricked him and claimed she could still develop interest in him. Maria plotted Malvolio's humiliation because he threatened that if she, Toby, and the rest of the household staff continued to cause problems in Olivia's residence, he would report to her and have them removed. During the intermission, I had to have Stephanie explain all of this to me because Shakespeare's prose was too dense for me to decipher the plot myself. After I was properly filled in, the second half made more sense and wrapped up the play's different storylines well enough. I could say that I enjoyed the play by the end, but if I hadn't been properly assisted, I would have left the theater confused by what I watched.

That said, I was wary about this play being, well, Shakespeare. The Bard has a reputation of haunting students in literature classes with illustrious dialogue that might as well be its own language. As excited as I was to see a play set in a locale that endeared me, I was unsure whether I would be able to understand what was even going on in the play.

I understood the skeleton of the story: Viola was disguising herself as a young man named Cesario to get close to Orsino, who insisted that "he" convince Olivia to return Orsino's affections. In the process, Viola had fallen for Orsino herself, and Olivia became attracted to Cesario. Olivia's louse of an uncle Toby was having fun hanging out and drinking with this Andrew guy. There was some other Cesario-looking guy who popped out of nowhere telling his companion Antonio he needed to go to Illyria (that is, Ybor City). Oh, and for some reason Olivia's handmaiden Maria wanted to make a fool out of the steward Malvolio by tricking him into thinking the lady he served secretly harbored affections for him.

What I was missing was the context. Somewhere in the characters' fanciful conversations, I should have figured out that our hero/ine Viola had survived a shipwreck (caused by a hurricane that slammed Miami while she was en route from Cuba, in this rendition), which led her to seek Orsino (a bootlegger) for work under the guise of Cesario. The guy that looked like Cesario was Viola's twin brother Sebastian, who also escaped the wreck, and Antonio a sea captain who had previously wronged Orsino's court. Andrew himself was interested in courting Olivia (whose "old money" status probably attracted many a man), and he would have left sooner if Toby hadn't tricked him and claimed she could still develop interest in him. Maria plotted Malvolio's humiliation because he threatened that if she, Toby, and the rest of the household staff continued to cause problems in Olivia's residence, he would report to her and have them removed. During the intermission, I had to have Stephanie explain all of this to me because Shakespeare's prose was too dense for me to decipher the plot myself. After I was properly filled in, the second half made more sense and wrapped up the play's different storylines well enough. I could say that I enjoyed the play by the end, but if I hadn't been properly assisted, I would have left the theater confused by what I watched.

That aside, I appreciated the aspects of the production that did make sense to me. As a setting, Ybor City during the Prohibition Era made the play feel simultaneously timeless and familiar. The 1920s was a timeframe close enough to feel contemporary and far enough to resonate with historical ambiance. The atmosphere was further established with a restaurant brick patio backdrop with a fern on a raised planter, iron-wrought benches, and old-style lamplights on either end of the stage. The ladies were garbed in skirts higher hemmed on the front and flowing in ruffles that bounced behind them with each step. The men wore tweed suits, bow ties, and suspenders. Orsino and his court kept pistols holstered at their hips. Printouts of newspaper front pages chronicling Ybor's role during Prohibition lined the theater entrance hallway.

The cast brought their characters to life with humorous stylings, acute facial expressions, and stirring music. Maggie Mularz tugged smugly at her blazer and followed up with her saucer-eyed, jaw-dropped delivery of Viola realizing Olivia was in love with her male alter ego, which drew immediate laughs from the audience. Jamie Jones brought his Andrew to life with a deep-bellied vibrato and exaggerated actions. In his pending dual with Cesario over stealing Olivia's heart, he posed and thrust his rapier in foppish overcompensation, and it was the more amusing that Cesario dropped his own rapier in fear with a clatter. Witnessing Giles Davies's stiff-postured, prim Malvolio unravel into a short-shorted, yellow-socked, love-struck fool sporting a most unsettling grin as he tried to acknowledge Olivia's supposed feelings for him was as riotous as it was oozing with second-hand embarrassment, but then seeing him later ashen and straight-jacketed in lockup made me well up with guilt.

Human moments like these were reminders that Twelfth Night was more tragedy than comedy, despite the snappy conversations and wacky physical hijinks such as Toby, Andrew, and Fabian hiding around lampposts, benches, and plants to listen to Malvolio read aloud Olivia's "love letter." Viola, Orsino, Olivia, and Sebastian had the least to lose, yet they were the ones who found their happily ever afters. Amid the hustle and bustle, the other characters lose their dignity, freedom, and security. As the events unfolded, Roxanne Fay's Feste observed the fallout, singing songs that touched the heart even without hearing all of the lyrics. Solemn wisdom resonated in her voice as she tapped a tambourine, a contemplative contrast not only to the fast-paced plot but the festive brass horn jazz recordings that blared between scenes -- a nice auditory touch and a callback to Ybor's famous Cuban Club. During the final song, Nick Hoop's Sebastian half-smiling at Michael McGreevy's Antonio hurt -- to think that Sebastian indirectly led to Antonio's arrest, yet he lived on in wedded bliss with Olivia! Gestures and cues like these helped Twelfth Night shine. If you dug through the Shakespearean speech, you would excavate characters with basic needs and wants that were either realized or manipulated before the audience's eyes.

Whether you're a neophyte or boast a doctorate in Shakespeare's works, you'll find a treat in Twelfth Night. The lick of local Tampa flavor, the cast's convincing character acting, and the obvious love and attention put into making the classic into Jobsite's own production combine in a tour de force of theater you would be loath to miss, especially as it approaches its final week on stage.

The cast brought their characters to life with humorous stylings, acute facial expressions, and stirring music. Maggie Mularz tugged smugly at her blazer and followed up with her saucer-eyed, jaw-dropped delivery of Viola realizing Olivia was in love with her male alter ego, which drew immediate laughs from the audience. Jamie Jones brought his Andrew to life with a deep-bellied vibrato and exaggerated actions. In his pending dual with Cesario over stealing Olivia's heart, he posed and thrust his rapier in foppish overcompensation, and it was the more amusing that Cesario dropped his own rapier in fear with a clatter. Witnessing Giles Davies's stiff-postured, prim Malvolio unravel into a short-shorted, yellow-socked, love-struck fool sporting a most unsettling grin as he tried to acknowledge Olivia's supposed feelings for him was as riotous as it was oozing with second-hand embarrassment, but then seeing him later ashen and straight-jacketed in lockup made me well up with guilt.

Human moments like these were reminders that Twelfth Night was more tragedy than comedy, despite the snappy conversations and wacky physical hijinks such as Toby, Andrew, and Fabian hiding around lampposts, benches, and plants to listen to Malvolio read aloud Olivia's "love letter." Viola, Orsino, Olivia, and Sebastian had the least to lose, yet they were the ones who found their happily ever afters. Amid the hustle and bustle, the other characters lose their dignity, freedom, and security. As the events unfolded, Roxanne Fay's Feste observed the fallout, singing songs that touched the heart even without hearing all of the lyrics. Solemn wisdom resonated in her voice as she tapped a tambourine, a contemplative contrast not only to the fast-paced plot but the festive brass horn jazz recordings that blared between scenes -- a nice auditory touch and a callback to Ybor's famous Cuban Club. During the final song, Nick Hoop's Sebastian half-smiling at Michael McGreevy's Antonio hurt -- to think that Sebastian indirectly led to Antonio's arrest, yet he lived on in wedded bliss with Olivia! Gestures and cues like these helped Twelfth Night shine. If you dug through the Shakespearean speech, you would excavate characters with basic needs and wants that were either realized or manipulated before the audience's eyes.

Whether you're a neophyte or boast a doctorate in Shakespeare's works, you'll find a treat in Twelfth Night. The lick of local Tampa flavor, the cast's convincing character acting, and the obvious love and attention put into making the classic into Jobsite's own production combine in a tour de force of theater you would be loath to miss, especially as it approaches its final week on stage.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed